Ramakrishna Ananda

Buddhism

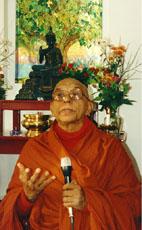

An interview with Reverend Mahathera Piyadassi

Reverend Mahathera Piyadassi arrived at my house in reddish-orange robes and brown sandals. He walked erectly from decades of meditation and discipline. Slightly above medium height, his head was clean shaven, his thin face shadowed with a hint of gray whiskers. Dark, intelligent eyes studied me. He was in his sixties perhaps and his expression seemed stern except that his lips were generous with smiles. He gestured gently as he spoke, his voice soft and rich, “This is a gift for you.”

He handed me a heavy object wrapped in blue silk. I opened the cloth to discover a crucifix fashioned in metal by a master craftsman.

“I knew you would like it,” he said, noticing my delight.

“I like it very much,” I replied, and admired the shining form of Christ for several minutes. Then my secretary placed the crucifix on a special shelf.

Educated at Nalanda College, the University of Sri Lanka, and Harvard University, Reverend Piyadassi is the senior monk at Vajirarama Monastery in Sri Lanka — a most beautiful country island on the southeastern tip of India. The equator passes near Sri Lanka.

Every other year this holy man travels around the world sharing the light of Buddhism, and he had paused in Southern California to make a series of loving lectures.

Reverend Piyadassi likes to be called “Bhante,” which is a name similar to “Swami,” or renunciant devotee.

We considered a number of possible snack foods and Bhante ultimately chose to have a little sliced fruit. We sipped juice and he consented to answer my questions about Buddhism. I was asking the right man because Bhante Piyadassi is the author of Buddhist Meditation, The Virgin’s Eye, and The Buddha’s Ancient Path, a significant discussion of Buddhism’s great teachings.

RA: Bhante Piyadassi, what is Buddhism, please?

He gestured gracefully, “Buddhism is not merely a religion; it is also a whole civilization with its historical background: it’s literature, art, and philosophy. Buddhism touches all aspects of human life — the social, economical, ethical, intellectual, spiritual, and mental development leading to enlightenment and nirvana. That is the goal of Buddhism — nirvana, or perfect peace and happiness.”

I reflected how hard it is to take any of the world’s religions and make them fit into a simple box. Obviously, a religion which is alive and helping humanity becomes deeply involved in all aspects of a society.

RA: Bhante, in essence, what are Buddha’s teachings?

“Buddha’s teachings are summed up in what came to be known as the Four Noble Truths. That is what the Buddha taught — the Four Truths.” He stopped, as if for emphasis.

“One, the fact that there is suffering in the world — that is to say, unsatisfactoriness or conflicts. The truth of suffering. Secondarily, this suffering has its causes. Suffering is not causeless — without cause. The Buddha, like a scientist, showed the cause of these sufferings. The cause is more subjective than it is objective. That is, man’s craving — his greed, hatred, or ill will and ignorance or delusion. These are the root causes of all our suffering.”

How similar these sufferings are to the views of ancient yogis, I thought. The great master Patanjali wrote that when a man ignores his true nature, he then experiences the five-fold suffering — ignorance, egotism, craving, fear, and possessiveness or greed.

RA: How can one deal with this suffering?

Bhante’s forehead creased slightly, “Suffering ceases when craving is stilled or removed. Then follows perfect peace or happiness — that is, the cessation of all suffering. This is the third Noble Truth.

“And the fourth truth is the path which leads to the cessation of suffering. This path consists of eight factors or eight limbs:

- Right Understanding

- Right Thought

- Right Speech

- Right Action

- Right Livelihood

- Right Effort

- Right Mindfulness

- Right Concentration

“These are the eight factors of Buddhism in practice,” Bhante smiled, then went on.

“Suffering and conflicts are like an ailment. There is the cause of the ailment, the cure, and the prescription. Buddha told his disciples, ‘I am like a physician, not for bodily ailments, but for mental ailments, mental maladies, of beings.’

“But,” Bhante added, “the recognition of th`is universal fact of suffering, however, is not a total denial of pleasure and happiness. The Buddha never denied happiness in life when he spoke of the universality of suffering. In Buddhist scriptures there is a long enumeration of the happiness that people are capable of enjoying. But all pleasures are impermanent, not lasting. A dispassionate study of Buddhism will tell you that Buddhism is a message radiating joy and hope — not a defeatist philosophy of pessimism.

“So, one who thinks deeply will interpret these Four Noble Truths as: One, suffering and conflicts to be understood; Two, the causes of suffering should be removed; Three, the cessation of conflict — nirvana — is to be realized; and Four, the Noble Eightfold Path is to be practiced or cultivated.”

RA: How beautiful and how succinct, I thought. “You are saying, then, the goal of Buddhism is nirvana?”

He nodded. “The goal of Buddhism is nirvana — deliverance of the mind. That is the final goal and cessation of all sufferings and conflicts — supreme happiness. But, also, the Buddha emphasizes the importance of the present life. In Buddhism we find the economic, social, ethical, intellectual, and mental or spiritual aspects. Buddhism emphasizes these aspects and the Buddha teaches all aspects of human life.”

How similar to Judaism, I thought, with its numerous directives about how to lead a spiritual life.

Bhante Piyadassi reflected a moment, then continued. “The Buddha speaks not only of a goal and life after death, but he also emphasizes (even more) the present life. For the Buddhist, this is not the only life.

“According to the Buddha, there were lives before birth and there will be lives after death. This is what we call re-becoming (or rebirth). We don’t use the word ‘reincarnation. 1 When one attains nirvana, there is no more re-becoming.”

RA: Bhante, I was fascinated with his answers, “How is a Buddhist fulfilled, or saved, or realized — whichever term you prefer to use?”

“You attain the goal by following the eight factors, the eight limbs. Buddhism, one may say, is a ‘do-it-yourself’ religion. The Buddha said: ‘You yourselves should put forth the necessary effort and work out your deliverance.’ The Buddha points out the way. It’s something like this: a man walking the road is suddenly confronted with a parting of the road and is unsure what to do. He looks around and sees a signboard and fingerpost and these give him directions. It’s left to the pedestrian — to you — to keep walking. So Buddha says, ‘I am like the signpost. I am a pointer and I show you the right path.’

“It’s left to the individual to follow the path,” he explained. “This path is the Noble Eightfold Path.

“Or, again, when you get sick you go to the physician. The physician will diagnose and find out the cause of your illness. Then he will give a prescription. It is left to you to see that the prescription is taken correctly.”

RA: I see. And what is the process of fulfillment for a Buddhist?

“Buddhism is a gradual process,” he answered. “The attainments do not come all at once; there is a gradual unfolding.

“You start,” he said, “with morality (sila). That is the starting point. Morality is the ABC of Buddhism. All ethics and morals have one function — to control the speech and action of man. Taming the tongue and controlling the bodily actions. That is the function of all ethics in Buddhism. So, you see, ethics is not an end in itself, but a means to an end.

“The second stage is developing the mind. We call it meditation or concentration (samadhi). We need a sharper weapon to tame the mind; so, established in morals or ethics, we go to meditation and concentration of the mind.

“Meditation is two-fold. The first, samatha, or samadhi, is calming the mind — taking an object of meditation and concentrating on it. This helps the mind to get calm, to collect itself, and to concentrate.

“The second aspect of meditation is vipassana, or panna, true wisdom or insight. This meditation helps one to see things as they really are, not as they appear to be. To see things in their true perspective — looking into life and not merely looking at it.

“So, there are three stages in the process of fulfillment: the first is the ethical stage which controls speech and action; the second stage is calming meditation, or concentration; and the third stage is wisdom or insight. These teachings, Buddha said, are excellent in the beginning, excellent in its progress, and excellent in its consummation.”

RA: How interesting, I thought. From the ethical, to the calming of the mind, to wisdom. “And what are the stages, levels, or states that you pass through as you become enlightened?”

Bhante spoke very seriously, but at first I thought he was teasing. “There are four stages,” he answered. “The first stage is sanctity, the second stage is sanctity, the third stage is sanctity, and the fourth stage is sanctity.”

I raised my eyebrows.

He smiled. “Let me explain. Human beings have so many defilements. At the first stage certain defilements are removed. One, unnecessary rituals and ceremonies are gotten rid of. Two, many doubts are also removed: doubts about Buddha, the teacher; doubts about the teaching; and doubts about the taught, the disciples, are gotten rid of.

“The man who attains the first stage of sanctity has no doubts about these three — the teachings, the teacher, and the taught. The suspicions and doubts are removed. One gets rid of the ‘I’ notion or the personality belief.

“Then in the second stage of sanctity, the person will cut down and attenuate, or lessen, the desire for sensual things, as well as hatred.

“In the third stage of sanctity there will be complete removal of sensuality and hatred.

“And in the fourth stage of sanctity one gets rid of the desire for higher worlds and the desire to be born in higher realms. Pride and conceit are no more. Restlessness is no more. Ignorance, the crowning corruption of all our madness, is also removed. One experiences perfect peace and happiness,” Bhante smiled lovingly at me.

I recalled the life of Gautama the Buddha: how Buddha was born a prince and lived in luxury, but felt compelled to seek enlightenment when he attentively observed the common sufferings of humanity — sickness, old age, and death. I remembered that Buddha renounced the world at age twenty-nine and, after six years of spiritual discipline, experienced his enlightenment — nirvana — which literally means freedom from bondage or corruption.

When I was in India, I’d had the privilege of visiting Bodh Gaya. After enjoying the beautiful serenity of the descendant of the Bodhi tree under which Buddha had received his enlightenment, I’d visited a number of the temples placed at that holy area by Buddhists from many nations. I recall being so happy that I broke into a dance while wandering from one temple to another and attracted a crowd. I had understood it was commonplace for devotees to dance in India and was surprised to find that a simple little dance could cause a lot of commotion and spectacle. In fact, contrary to what I had been told before going to India, I did not see anyone dancing informally about the countryside.

It was interesting to be in India where most Hindus call Buddha an incarnation — a divine descent of consciousness — while all the Buddhists insist that Buddha was definitely not an incarnation. That was quite a pleasant perplexity.

took advantage of my opportunity and asked one of the world’s greatest spokesmen on Buddhism to enlighten me about the Buddha.

RA: Bhante, do Buddhists consider Buddha a divine incarnation?

“No,” he said, “a noteworthy characteristic that distinguishes the Buddha from all other religious teachers is that he was a human being. Not just another man or philosopher, but an extraordinary man, a unique being, a man par excellence. The Buddha cultivated his mind to the highest possible state. This is called enlightenment. The title of Buddha means the enlightened one. Buddha means ‘he is immune to all evil.’

“The Buddha was known as Bodhisattva before he became a Buddha. Bodhisattva means ‘one who is aiming at enlightenment, one who is bent on enlightenment.’

“So, before he became the Buddha he was a Bodhisattva. He took birth for many, many, many lives. He had to go through and cultivate ten essential qualities to a high standard before becoming the Buddha. These ten qualities are:

- Generosity

- Morality or Virtue

- Renunciation

- Wisdom

- Effort

- Forbearance

- Truthfulness

- Determination

- Loving Kindness

- Equanimity

“These are called the ten paramita, or ten essential qualities — virtues of high standard. These are the ten qualities that a Bodhisattva cultivates life after life. To attain enlightenment he must cultivate the ten paramita. This is why we say he took birth again and again. As you know, we do not use the word reincarnate because Buddhists do not believe that there is a permanent entity or ‘I’ self to take birth. Buddhism uses the word re-becoming rather than reincarnating — coming again life after life.

“So, one cultivates the ten qualities to become Buddha. The Buddha is not an incarnation of God or Brahma or any external agency. As the Buddha was a human being, his teaching was anthropocentric, or man-centered, and not theocentric — God-centered. The Buddha is not a God, or Creator, who punishes the ill deeds and rewards the good deeds of the creatures of his creation.

“The Buddha attributed all his attainments and achievements to human effort and human wisdom or understanding. Through personal experience he understood the supremacy of man.

Bhante’s remarks made me understand how difficult it is for people of the West to be fair to Buddhism and strive to understand it deeply. It is difficult to conceive of an openly man-centered religion unless one studies the ten essential qualities and the eight limbs of Buddhism.

RA: Bhante, I’ve long treasured a walking conversation I enjoyed with a Zen Buddhist at Bodh Gaya in India. Here in the U.S., we are fascinated with Zen. Please tell me, Bhante, what exactly is Zen?

“The word Zen sounds Japanese, but Zen came from India,” Bhante answered. “We have a word in the Pali language — Pali is the language Buddha used — jhana. And in the other ancient language of India, Sanskrit, the word is dhyana. Ihana or dhyana means meditative absorption.

“So,” he continued, “when an Indian Buddhist monk called Bodhi Dharma went to China, the Chinese people pronounced the word not as jhana, but as chan. Even today, Chinese say chan. Now, when this chan, this way of meditative absorption was taken to Japan, the name was Japanized and became zen. So, the original word is jhana; in Sanskrit it is dhyana; Chinese call it chan; and Japanese call it zen.

RA: Good, I said, then Zen is a method of meditative absorption.

“All meditation,” he replied.

RA: Now, what is the difference, if any, between Zen and regular Buddhism?

“Mainly,” Bhante leaned forward, “Zen is a meditation sect. It specializes in meditation and aims at enlightenment. But in Buddhism, generally, before coming to meditation you must cultivate morality. It’s a gradual process, a gradual training, and a gradual doing. First morality, then concentration, and then go inside to meditation. In Buddhism the aim is enlightenment and deliverance, while the aim of Zen is enlightenment.”

RA: But wouldn’t enlightenment in Zen bring deliverance, too?

“It can,” he nodded slowly, “but only the collected mind, the contented mind, can see things as they really are and not as they appear to be.”

“So,” I responded, “a person practicing Zen might not have enough development to experience full realization.”

“In Buddhism,” Bhante reiterated, “you first have to bring your speech and action under control — that is morality. Then you go to the calming meditation; and, then, proceed to the inside meditation. Through inside meditation you find your true wisdom, your right understanding which leads to deliverance and enlightenment.”

RA: Zen doesn’t do a gradual process. That’s the difference, Bhante?

“Not a gradual process, he smiled at me. “They try to get enlightenment from the very beginning. Of course their aim — in itself — leads to some purification. Zen is a meditation sect.

“The books written about Zen by Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki are very good,” Bhante added.

RA: And, dear Bhante, what is a Buddhist’s attitude toward other religions? I asked.

“All religions, major and minor, have their origin in the East. Today there are five world religions: Buddhism, Christianity, Hinduism, Islam, and Judaism.

“Buddhists do not belittle other faiths in order to extol their own. Even the Buddha, when he had time, visited other religious centers and had friendly talks and discussions with them. Two hundred years after Buddha passed away, King Asoka of India wrote in his inscriptions that, ‘People should respect other religions.’

“If you wish to keep religious harmony, it is better not to interfere with the doctrinal aspects of religion but find out the common factors. In other words, we must find out the areas of concern which the religions share in common. For instance, peace, social justice, removal of poverty, protection of the natural environment from destruction by pollutants and industry, etc. Representatives of different religions should meet and discuss and discover the essential similarities and differences between the religions.”

RA: How succinct, I mused, wishing all could hear what Bhante was saying. Two more questions, Bhante, and then we must leave. First, what is the Buddhist view of man?

“Of course,” Bhante responded, “in Buddhism the pride of place is given to man, because it is a man who becomes a Buddha. All can become Buddhas provided they cultivate the necessary qualities that go to make a Buddha.

“So, Buddhahood is not the prerogative of a chosen few. The Buddha seed is in all men, so each man is like a box of matches. In a box of matches you cannot see the flame but you can, through friction, get the flame. Man works out his deliverance through effort, and bringing out the light.

“Human beings can reach the highest or go down to the lowest. That is each man’s lookout. It is left to man to go up or down. There is no compulsion or coercion in Buddhism. It’s a free religion. Buddha gives the first charter of free inquiry in a special discourse, called the Kalama Sutra. Buddha says you have the right to inquire, to scrutinize, and to examine.”

RA: In Bhante’s discussion he had not mentioned the relationship of God to man and I wanted to fully understand how God functioned in Buddhism. What is the Buddhist view of God? I asked.

“When you speak about God, there are two types. One is the Creator God: the permanent, everlasting God. Then there are what are called the deities, or celestial beings, or devas. In Buddhism we speak about the deities. They are not permanent or everlasting. The God that theistic religion speaks of is a permanent, everlasting God and it is this God who punishes the evil deeds and rewards the good deeds of the creatures of his creation. This concept is not in Buddhism.

“In Buddhism there is a belief in the deities, or celestial beings. The Buddha was not against the word God, or soul, but he does not approve of anything permanent or everlasting. Only nirvana, which is Supramundane, is permanent. Looking at it from a purely scientific standpoint, nothing is permanent in this world.”

I told Bhante I was going to strive to quote him as accurately as I could and trust that his words would bless those who entered into the chapter on Buddhism appreciatively and with open hearts. While I so appreciated his clear explanations of Buddhism, I knew Bhante was sharing a view of life which only much study, discipline, meditation, and direct experience could truly reveal.

RA: Reluctantly, I asked my last question, Finally, how do you, Bhante, see a more peaceful world occurring?

Bhante Piyadassi gazed thoughtfully at me for a while and then his clear, mellow voice replied, “To bring about peace and harmony in this world, my viewpoint is this: people have peace conferences, discussions, meetings, and all sorts of activities, but the whole thing is really in the hands of a few powerful people in powerful countries. There should be a radical change in the hearts of the people who are at the helm of affairs, otherwise you cannot bring about peace. We may talk about peace and have conferences everywhere, but what good are conferences unless the powerful people give a thought to world peace? Only they can bring about peace and harmony. We can write about peace and have discussions, but the whole thing is with these few powerful people.

“I understand that when people went to Albert Einstein and asked, ‘What do you think about the Third World War?,’ he reportedly answered, ‘I don’t know about the Third World War, but I’ll tell you about the Fourth.’ They asked him, ‘What is it? What is it? What is it?’ Einstein said, ‘When you go to wage the Fourth World War, it will be with sticks and bows and arrows. We’ll be back to primitive man.’ Einstein explained what the Third World War is going to do — complete devastation.

“So, all this peace and harmony can be brought about by only a few powerful statesmen of the powerful countries of the world. Only they can bring about peace and harmony.”

Bhante stood. It was time to go. He put on his cloak and rode with me to his lecture. “Ninety percent of Buddha’s teachings are about the mind,” he told his audience. He went on to say that the goal of Buddhism — whether Zen, Mahayana, Tibetan, or Theraveda — is the enlightenment called nirvana. “As a result of this supreme state of higher consciousness, ignorance, arrogance, fear, and anger fall away. One no longer distorts one’s vision of life or of the self,” he emphasized. Bhante explained that all these different schools of Buddhism followed the same Sakyamuni Buddha.

All life’s problems, Bhante said, can be reduced to one simple problem, that of dukkha, suffering or unsatisfactoriness, or conflicts. The solution put forward by the Buddhas or Enlightened Ones of all ages is the Noble Eightfold Path. The efficiency of the path lies in the practice of it. The Buddha’s path still beckons the weary pilgrim to the haven of nirvana’s security and peace.

But, he smiled gently, “Buddhists do not spend too much time inspiring others about the greatness and glory of nirvana. The mind, ego, and emotions are totally unable to understand the reality of that sovereign, wondrous, illimitable freedom and well being!”

When he finished speaking, I thought about nirvana, about that great and total no-thing-ness into which every being would ultimately dissolve. Bhante had made me feel its peace. And, I remembered how the Buddha, the prince of compassion, had said he would not enter into nirvana till every creature had been liberated. I savored the thought of the beautiful Buddha and I thanked Bhante for his great wisdom.

Each week you’ll discover different approaches and techniques which will lead to a more satisfying, spiritual life. Watch for two new videos and one new talk every Wednesday! View our Recent Additions.

Each week you’ll discover different approaches and techniques which will lead to a more satisfying, spiritual life. Watch for two new videos and one new talk every Wednesday! View our Recent Additions.